Anglotopian Dreams: The Ideational Relationship Between Science Fiction and the Anglophile Milieu

By Paul & Phillip Darrell Collins

The Waking Dreams of Sci-fi “Prophets” and Sociopolitical Utopians

There is an interesting ideational nexus where sociopolitical Utopianism and the science fiction literary genre intersect. While science fiction has not always been taken seriously as a literary genre, it has acted as a repository for several of the ideas espoused by serious sociopolitical Utopians. The ideational relationship has been largely a reciprocal one where Utopian theoreticians influence sci-fi authors and vice versa. This ideational relationship is partially attributable to a shared spiritual heritage. Nowhere is this shared heritage more demonstrable than with Cecil Rhodes’ Anglophile network and the “prophets” of British science fiction.

Both were deeply tinctured by a Gnostic cosmological resentment and autotheism. Dissatisfied by the established facts of reality, both inhabited dream worlds where their Utopian fictions reigned supreme. While the likes of Wells, Stapledon, and Clarke rendered this dream world as attainable with colorful prose, the Anglophile network invested its vast reservoirs of political, financial, and social capital in the tangible enactment of that world. Ultimately, both the Anglophile network and the British sci-fi “prophets” maintained the same eschatological hope: an Anglotopia.

Fiction’s Revolt Against Fact

Traditionally, the binary of fact and fiction has been understood as a dichotomy. On the simplest level, fact can be defined as “that which is” while fiction can be defined as “that which is not.”

The two conditions are mutually exclusive and never shall the twain meet. Yet, there are those who are so thoroughly seduced by the enticements of their Utopian fictions that they actually attempt to re-sculpt reality to reflect their fantasies. These fantasies are inspired by a virulent cosmological resentment. The fantasizers conflate the cosmos with the postlapsarian ills that afflict it, thereby maligning the created order and lapsing into the same docetistic cosmological attitude espoused by the ancient Gnostics. They only deviate from their ancient antecedents in regards to how they deal with their present habitation.

Where the ancient Gnostics sought to escape the world, the new Gnostics seek to recreate it. They intend to supplant the facts of established reality with the fictions of their docetistic minds. Because these new Gnostics loathe the cosmos, they reject facts in favor of Utopian fictions. They actively demolish “that which is” in hopes of enshrining “that which is not” as the ultimate reality. They have no desire to believe what they see. Instead, they see what they believe, which is a vaporous schematic for their Utopia. Such a revolt against reality is exemplified by the principles of Hegel’s dialectical logic. Herbert Marcuse condensed these principles into a single relativistic aphorism: “That which is cannot be true” (qutd. in Katsiaficas and Emery, “Critical Theory and the Limits of Sociological Positivism”). Elaborating upon this dictum, Marxist academicians George Katsiaficas and Mary Lou Emery write:

“In other words, our existing society of racism, genocide, and possible nuclear holocaust cannot be the “truth” of human existence. Truth must lie somewhere else, not in the facts of the given reality, but in the negation or transcendence of those facts. Truth lies in the attempt to go beyond this reality to a better world. Thus, truth lies in our attempt to change the world, in our critique of the established reality.” (Ibid)

Just as the ancient Gnostics confused the consequences of the Fall with the very act of creation, Katsiaficas and Emery erroneously conflate “racism, genocide, and possible nuclear holocaust” with reality. Instead of recognizing “racism, genocide, and possible nuclear holocaust” as the products of man’s own disordered will, they ascribe such evils to the cosmic order itself. This Gnostic proclivity to associate extraneous evils with the otherwise good creation underpins the Marxist attempt to “go beyond this reality to a better world.” Instantiation of the Marxist fiction, namely a classless Utopia, stipulated the negation of the “facts of the given reality.” Because the “facts” (genocide, racism, and nuclear holocaust) were allegedly inseparable from reality, all that constituted reality had to be negated. The negation of reality typically entailed the imprisonment and/or extermination of any opposition. Again, the Hegelian aphorism declares: “That which is cannot be true.” On the Hegelian view, truth could be found not in established reality, but in the “attempt to change the world.” Once established reality was negated, the Marxists were free to populate the world with simulacra, bodied forth by grotesque parodies of once legitimate institutions.

This anti-reality crusade also underpins the massive Utopian project of the global oligarchical establishment, which, incidentally, created communism as an instrument for the consolidation of their power. Like their Marxist progenies, the global oligarchs uphold the Hegelian mandate: “That which is cannot be true.” For the global oligarchs, that which is (a world of sovereign nation-states) cannot be true. On the globalist view, evil is imputed not to man’s disordered will, but to the social cosmos. Because the sovereign nation-state is the chief unit by which the social cosmos is ordered, it must be swept away. Truth is found in the globalist attempt to change the world, which involves amalgamating nations into a single supra-national entity. Such a global arrangement has been euphemistically dubbed a New World Order.

It is a foregone conclusion that such anti-reality crusades are doomed to failure. After all, the crusaders reject the structure of reality. This rejection compels the crusaders to create a second reality or, as Eric Voegelin has called it, a “dream world.”

The dream world is a Utopian schematic that the anti-reality crusader strives to impose upon reality through various forms of activism and political programs. For the globalists, building the dream world includes the enacting of economically deleterious trade agreements, reversing growth in industrialized nations, culling “surplus populations” through various Malthusian schemes, imposing technological apartheid on developing nations, and eroding national sovereignty through dubious international treaties. It is the globalist’s eschatological conviction that these programs operating in an alchemical synergy will expunge this ontologically deficient world’s chief aberration: heterogeneity.

Charlie Skelton summarizes the globalist aversion to heterogeneity: “The ideology of globalization perceives otherness as an evil to be overcome. Constantly merging and acquiring, dominating and consolidating, to the point of singularity” (“Silicon Assets”).

The dream world envisioned by the globalists is one bereft of differentiated beings. For the globalist, “otherness” is a corruption. Whether conveyed tacitly or explicitly, this animus toward differentiation stems from a distinctly monistic normative conviction: All must be one. Through the eyes of the oligarchs, differentiation is symptomatic of a cosmic corruption. The Eschaton envisioned by humanity’s aspirant hegemons is “pure” because it is undifferentiated. It is, in essence, an immanentized version of the Gnostic Pleroma.

On the globalist view, an outward expression of the cosmic corruption allegedly afflicting humanity is political and economic differentiation. Differing political and economic systems confound the elite’s efforts to amalgamate nation-states into a single, interdependent system. For the elite, such a world order would constitute a new Eden. Supposedly, under such Utopian conditions, man will undergo a glorious transfiguration and achieve apotheosis. To that end, the globalists have created several organizations and agencies devoted to promoting world government.

Pax Britannia: The Dream World of Cecil Rhodes

Arguably, this crusade was, to a sizable extent, inspired by a 19th-century Anglophile network. In support of this contention, one needs only to cite the origins of one particular globalist think tank. Chief among the various globalist organizations actively pursuing the homogenization of otherwise disparate political and economic systems is the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

The CFR was merely a stateside branch of the Royal Institute for International Affairs (RIIA) (Quigley 132-33). In turn, the RIIA was founded by the Round Table Groups (132-33). These Round Table Groups owed their existence to a directive presented in the last will and testament of British imperialist Cecil Rhodes. This directive mandated the formation of a secret network committed to the imperialist objectives of the British Empire. Rhodes’ Weltanschauung was inspired by a speech delivered by John Ruskin at Oxford in 1870.

Embedded within the body of this speech was the clarion call of a new imperialism. This new imperialism, unlike earlier imperialist models, possessed a foundation of pseudo-morality and social reform. Ruskin was a true believer in this new imperialism and preached its tenets with the fervor of a missionary evangelizing on behalf of the Gospel. Ruskin used his professorship chair of fine arts at Oxford as a pulpit for his evangelization effort. Carroll Quigley elaborates:

“The new imperialism after 1870 was quite different in tone from that which the Little Englanders had opposed earlier. The chief changes were that it was justified on grounds of moral duty and social reform and not, as earlier, on grounds of missionary activity and material advantage. The man most responsible for this change was John Ruskin.

Until 1870 there was no professorship of fine arts at Oxford, but in that year, thanks to the Slade bequest, John Ruskin, was named to such a chair. He hit Oxford like an earthquake, not so much because he talked about fine arts, but because he talked also about the empire and England’s downtrodden masses, and above all because he talked about all three of these things as moral issues. Until the end of the nineteenth century the poverty-stricken masses in the cities of England lived in want, ignorance, and crime very much as they have been described by Charles Dickens. Ruskin spoke to the Oxford undergraduates as members of the privileged, ruling class. He told them that they were the possessors of a magnificent tradition of education, beauty, rule of law, freedom, decency, and self-discipline but that this tradition could not be saved, and did not deserve to be saved, unless it could be extended to the lower classes in England itself and to the non-English masses throughout the world. If this precious tradition were not extended to these two great majorities, the minority of upper-class Englishmen would ultimately be submerged by these majorities and the tradition lost. To prevent this, the tradition must be extended to the masses and to the empire.” (130)

For a group of Oxford undergraduates, Ruskin’s message was a source of inspiration, similar to the way the Torah, the Koran, and the Bible inspired their respective devotees. For better or worse, Ruskin’s new imperialism won disciples.

Undergraduate Cecil Rhodes appears to have been the most fanatically devoted of these disciples. Just as the Pope is regarded as the head bishop over the church by Roman Catholics, Quigley regards Rhodes as Ruskin’s chief disciple and the primary minister of the new imperialism. Ruskin’s message of salvation, which permeated the ruling class tradition, inspired Rhodes to undertake several imperialist projects. The fortune generated by these projects would serve as the early financial backbone of the new imperialism. By realizing Ruskin’s utopian vision, Rhodes hoped to see the creation of a world dominated by the English ruling class. Quigley writes:

“Ruskin’s message had a sensational impact. His inaugural lecture was copied out in longhand by one undergraduate, Cecil Rhodes, who kept it with him for thirty years. Rhodes (1853-1902) feverishly exploited the diamond and goldfields of South Africa, rose to prime minister of the Cape Colony (1890-1896), contributed money to political parties, controlled parliamentary seats both in England and in South Africa, and sought to win a strip of British territory across Africa from the Cape of Good Hope to Egypt and to join these two extremes together with a telegraph line and ultimately with a Cape-to-Cairo Railway. Rhodes inspired devoted support for his goals from others in South Africa and in England. With financial support from Lord Rothschild and Alfred Beit, he was able to monopolize the diamond mines of South Africa as DeBeers Consolidated Mines and to build up a great gold mining enterprise as Consolidated Gold Fields. In the middle 1890’s Rhodes had a personal income of at least a million pounds sterling a year (then about five million dollars) which was spent so freely for his mysterious purposes that he was usually overdrawn on his account. These purposes centered on his desire to federate the English-speaking peoples and to bring all the habitable portions of the world under their control. For this purpose Rhodes left part of his great fortune to found the Rhodes Scholarships at Oxford in order to spread the English ruling class tradition throughout the English-speaking world as Ruskin had wanted.” (130-31)

Rhodes was not the only convert to Ruskin’s Anglophilic evangel. Several other adherents became associated with Rhodes. This network of Ruskin disciples would establish a secret society devoted to the cause of British imperialism and, ultimately, global government. Quigley elaborates:

“Among Ruskin’s most devoted disciples at Oxford were a group of intimate friends including Arnold Toynbee, Alfred (later Lord) Milner, Arthur Glazebrook, George (later Sir George) Parkin, Philip Lyttelton Gell, and Henry (later Sir Henry) Birchenough. These were so moved by Ruskin that they devoted the rest of their lives to carrying out his ideas. A similar group of Cambridge men including Reginald Baliol Brett (Lord Esher), Sir John B. Seeley, Albert (Lord) Grey, and Edmund Garrett were also aroused by Ruskin’s message and devoted their lives to the extension of the British Empire and uplift of England’s urban masses as two parts of one project which they called “extension of the English-speaking idea.” They were remarkably successful in these aims because of England’s most sensational journalist William Stead (1849 – 1912), an ardent social reformer and imperialist, brought them into association with Rhodes. This association was formally established on February 5, 1891, when Rhodes and Stead organized a secret society of which Rhodes had been dreaming for sixteen years. In this secret society Rhodes was to be leader; Stead, Brett (Lord Esher), and Milner were to form an executive committee; Arthur (lord) Balfour, (Sir) Harry Johnston, Lord Rothschild, Albert (Lord) Grey, and others were listed as potential members of a “Circle of Initiates;” while there was to be an outer circle known as the “Association of Helpers” (later organized by Milner as the Round Table organization). Brett was invited to join this organization the same day and Milner a couple of weeks later, on his return from Egypt. Both accepted with enthusiasm. Thus the central part of the secret society was established by March 1891. It continued to function as a formal group, although the outer circle was, apparently, not organized until 1909-1913. This group was able to get access to Rhodes’ money after his death in 1902 and also to funds of loyal Rhodes supporters like Alfred Beit (1853-1906) and Sir Abe Bailey (1864-1940). With this backing they sought to extend and execute the ideals that Rhodes had obtained from Ruskin and Stead. Milner was the chief Rhodes Trustee and Parkin was Organizing Secretary of the Rhodes Trust after 1902, while Gell and Birchenough, as well as others with similar ideas, became officials of the British South Africa Company. They were joined in their efforts by other Ruskinite friends of Stead’s like Lord Grey, Lord Esher, and Flora Shaw (later Lady Lugard). In 1890, by a stratagem too elaborate to describe here, Miss Shaw became Head of the Colonial Department of the Times while still remaining on the payroll of Stead’s Pall Mall Gazette. In this past she played a major role in the next ten years in carrying into execution the imperial schemes of Cecil Rhodes, to whom Stead had introduced her in 1889.” (131-32)

When Rhodes died, the continuation of his imperialistic mission fell upon the shoulders of chief Rhodes Trustee Alfred Milner. It is with this development that the Anglophilic origins of the CFR come into focus. Under Milner’s coordination, the Rhodes network would establish the stateside surrogate organization that would adopt the appellation of the CFR. Quigley continues:

“As governor-general and high commissioner of South Africa in the period 1897-1905, Milner recruited a group of young men chiefly from Oxford and from Toynbee Hall, to assist him in organizing his administration. Through his influence these men were able to win influential posts in government and international finance and become the dominant influence in British imperial and foreign affairs up to 1939. Under Milner in South Africa they were known as Milner’s Kindergarten until 1910. In 1909-1913 they organized semisecret groups, known as Round Table Groups, in the chief dependencies and the United States… In 1919 they founded the Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House) for which the chief financial supporters were Sir Abe Bailey and the Astor Family (owners of The Times). Similar Institutes of International Affairs were established in the chief British dominions and in the United States (where it is known as the Council on Foreign Relations) in the period of 1919-1927.” (132-33)

The CFR would eventually transmogrify itself into a de facto appendage of the United States government in 1939 with a project known as the War and Peace Studies Project. James Perloff describes this penetration of the halls of officialdom:

“In September 1939, Hitler’s troops invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany; World War II had begun.

Less than two weeks later, Hamilton Fish Armstrong, editor of Foreign Affairs, and Walter Mallory, the CFR’s executive director, met in Washington with Assistant Secretary of State George Messersmith. They proposed that the Council help the State Department formulate its wartime policy and postwar planning. The CFR would conduct study groups in coordination with State, making recommendations to the Department and President. Messersmith (a Council member himself) and his superiors agreed. The CFR thus succeeded, temporarily at least, in making itself an adjunct of the United States government. This undertaking became known as the War and Peace Studies Project; it worked in secret and was underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation. It held 362 meetings and prepared 682 papers for FDR and the State Department.” (64)

The CFR used its temporary position as a government adjunct to spread its members throughout the government. The State Department was particularly infested. In fact, the CFR’s influence over State led to what can only be described as the privatization of foreign policy. American foreign policy became little more than a vehicle for the agendas of bankers, corporations, globalists, and elitists. Thus, the origins of this major purveyor of globalism were distinctly Anglophilic.

This Anglophile network may have found its origins in the pages of fiction. Duncan Bell, the University of Cambridge Professor of Political Thought and International Relations, observes that Rhodes’ “most innovative contribution to racial utopian discourse” was the suggestion “that a secret society was necessary to undertake the epic task” of uniting the world under Anglo-Saxon rule (Bell 134). This secret society, of course, became a reality and produced the Anglophile constellation described earlier. Bell describes the secret society envisioned by Rhodes:

“[Rhodes’] model was the Society of Jesus. Its members scattered throughout the Anglo-Saxon world, such a society would spread the gospel of racial superiority, recruiting the best and the brightest of each generation to further the unionist cause. It would have two interwoven objectives: bringing the “whole uncivilized world under British rule” and the “recovery of the United States.” (134)

Where did Rhodes derive the idea of such a secret society? The source of inspiration may have been identified in a recommendation made by Rhodes to fellow Anglophile network participant and journalist W.T. Stead. Bell writes:

“Rhodes encouraged Stead to read An American Politician, an1884 novel by the popular American writer F. Marion Crawford. The reason is clear. Very loosely based on the election of Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877, the tale focuses on a politician driven by an overriding sense of duty and aided by an Anglo-America secret society.” (134)

According to Bell, Crawford “was best known as a writer of ghost stories” (134). Crawford, however, demonstrated a knowledge of how covert power works in his 1897 novel Corleone, which has been called “the first major treatment of the Mafia in literature” (Francis Marion Crawford”). Crawford also concluded his 1900 novel Rulers of the South with a chapter about the Sicilian Mafia (ibid). Given Crawford’s comfort with topics such as secret societies and organized crime, it seems fitting that his literary work would inspire Rhodes to establish covert political circles dedicated to the realization of Anglotopia.

Envisioning Anglotopia: Rhodes’ Dream World Distilled as Sci-fi

The very same Anglophile milieu that gave rise to the CFR also carried on a reciprocal exchange of ideas with the science fiction literary genre. For several years, science fiction authors would draw inspiration from Anglophile theoreticians and vice versa. It is difficult to determine with whom this exchange began. Did it begin with the Anglophile theoreticians or the science fiction authors? While the answer remains elusive, it is a well-established fact that the progenitor of the Anglophile network, Rhodes, was inspired by a “universal history” penned by William Windwood Reade. Reade authored The Martyrdom of Man, a secular theodicy advancing the neo-Darwinian contention that man could be perfected through the painful, yet necessary evolutionary process. Robert Rotberg synopsizes The Martyrdom as follows:

“William Windwood Reade, the then-obscure British Darwinian, influenced Rhodes’ search for understanding. An unsuccessful novelist, Reade visited West Africa twice in the 1860s, the second time while Rhodes was in Natal, and published The Martyrdom of Man in 1872. Begun as an attempt to revise England’s accepted and critical view of the contribution of Africans to human civilization, The Martyrdom became a universal history of mankind, with long sections on Rhodes’ favorite mysteries: ancient Egypt, Rome, Carthage, Arab Islam, and early Christianity. The Martyrdom consisted of the kind of late nineteenth-century pseudo-science that appealed to Rhodes. It was larded with philosophically impressive arguments about the true “meaning” of man based on the post-Hegelian as well as neo-Darwinian notion that man’s suffering on earth (his martyrdom) was essential (and quasi-divinely inspired) in the achievement of progress. Man was perfectable, but only by toil. He could not be saved, nor would his rewards be heavenly, for Reade was a pre-Tillichean Gnostic who believed in God’s existence but, at the same time, not in deism and certainly not in the accessibility of an anthropomorphic Christian God. The rewards of man were in continuing and improving the human race. “To develop to the utmost our genius and our love, that is the only true religion,” wrote Reade. (99-100)

While The Martyrdom doesn’t quite qualify as a piece of science fiction, Rotberg does liken Reade to Jules Verne because he: “prophesied a locomotive force more powerful than steam, the manufacture of flesh and flour chemically, travel through space, and the discovery by science of a destructive force which would be so horrible as to end all wars” (100). Such “prophesying” would become commonplace among science fiction authors. James Herrick explains:

“In a Saturday Review interview, influential science-fiction editor John Campbell argued that the genre’s principal social role was as “prophecy”—by which he did not mean simply foretelling the future, but also preparing its audiences to embrace a particular vision for the future. The man who shaped the careers of such science-fiction greats as Asimov, Heinlein, van Vogt, and Doc (E.E.) Smith assigned to science fiction an essentially moral or spiritual role. (Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs 30)

Campbell’s contention that “prophecy” constituted science fiction’s chief social role underscores the genre’s imposing normative potential. Affirmation of this potential can be found in a May 2005 New York Times article entitled “Sci-Fi Synergy.” Therein, author Edward Rothstein states: “A genre that 80 years ago was on the margins is now, at least in its cinematic incarnations, at the very center of culture” (qutd. in Herrick, Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs 22). Elaborating on the normative impact that the sci-fi genre wields in its cinematic incarnations, Herrick writes: “Science fiction has emerged as a formidable social force with a worldwide reach and an international audience in the hundreds of millions. Seven of the twenty most profitable movies ever produced fall within the science fiction genre” (22). Given its undeniable influence upon culture, science fiction clearly possesses the potential to affect audiences in a normative capacity.

In her essay over science fiction’s normative power, Martha A. Bartter makes it clear that science fiction does not necessarily “make people behave in ways they otherwise would not” (Bartter 169). This perception of science fiction typically engenders “either the tacit justification for propaganda, or the reverse, the explicit justification for censorship” (169). However, it is through the presentation of possibilities that the normative power of science fiction is most effectively demonstrated. Bartter explains:

“[F]iction can represent possibilities for action to a large number of people in such a way that they can more clearly perceive possible choices and the various socio-cultural sanctions attached to those choices. The very act of considering choices irrevocably alters our assumptions about ways we may act, and since actions derive from assumptions (in the sense that both doing and choosing not to do must be considered actions), fiction can indeed endanger the status quo. The censors are right—for the wrong reasons.” (169)

Indeed, considering various choices and their concomitant socio-cultural sanctions can call the status quo into question. The propositional content of a fictional work can either partially or completely conflict with the dominant cultural conventions of any given society. Audiences that are exposed to such propositional content will invariably consider choices that could potentially revise the status quo. A prescription can be rendered more tenable within the body of an imaginative narrative. Once fiction starts making such prescriptions, it becomes normative in character.

Yet, Bartter discerns an “inherent ambiguity” to normative fiction (169). As products of specific time periods, fictional tales tend to uphold some of the cultural norms of their respective historical eras. Yet, simultaneously, fictional tales can present possibilities that are rendered feasible through elements such as characters, settings, themes, etc. When audiences are presented with these fictional devices, they tend to suspend their critical faculties and accept fantastical propositions. In so doing, audiences entertain alternative ideas and values. Propositions are tangibly enacted and a “new consensus” is considered. Bartter elaborates:

“On the one hand, every fiction arises from a particular time and place; it demonstrates to its hearers/readers a tacit consensus regarding cultural norms. On the other hand, and at the same time, it can introduce to its readers possibilities that they previously did not know or had not considered, and make these possibilities vividly “real” by fictional devices such as plot, character, setting, etc. Through a “willing suspension of disbelief,” readers conduct socio-cultural gedankenexperimente: they test how such ideas might work out in reality and what effects they might produce, and consider the possibility of a new consensus.” (169)

Gedankenexperimente is the German word for “thought experiment.” The famous science fiction writer and editor John W. Campbell proposed that sci-fi presented an “unparalleled opportunity for socio-cultural thought experiments” (183). Through such experiments, the ideas of a particular fiction are tested and aspects of the current culture are called into question. As the experiment progresses, revisions in the status quo might be entertained or even enacted. If certain cultural norms happen to be amended or jettisoned along the way, then the dominant culture could witness the emergence of a “new consensus.” Thus, the question is not whether science fiction can change society, but how? The nature of the cultural shifts induced by sci-fi depends upon the nature of the normative claims that inspired them. The more dubious an author’s normative claims, the more ominous their existential consequences.

While The Martyrdom is not really considered a work of science fiction, the book is replete with the same sort of fanciful technology forecasts that one finds in the pages of the fantastical genre. More significantly, it explored a theme that pervaded British science fiction: humanity’s inexorable evolutionary advancement toward perfection. Of this theme, Herrick writes:

“Inevitable human progress through evolutionary processes is a theme in some of the most imaginative and persuasive science fiction. It is particularly important to the works of three pillars of British science fiction: H.G. Wells (1866-1946), Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950), and Arthur C. Clarke (b. 1917). That Wells would have devoted attention to human evolutionary advancement is not surprising considering that he was a student at Huxley’s London School of Science. (The Making of the New Spirituality: The Eclipse of the Western Religious Tradition 145)”

Arguably, Reade is responsible for popularizing the evolutionary theme that would preoccupy the “three pillars of British science fiction.” Yet, it is with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle that one finds the clearest example of Reade’s influence upon British sci-fi scribes.

Doyle wrote several pieces of science fiction, including The Lost World and his Professor Challenger stories. Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes novel, The Sign of Four, features a glowing reference to Reade’s The Martyrdom. While discussing the literary quality of some letters with Watson, Holmes states: “Let me recommend this book, —one of the most remarkable ever penned. It is Winwood Reade’s ‘Martyrdom of Man.’” Clearly, Doyle was familiar with Reade and he may have even expressed some affinity for The Martyrdom vicariously through the beloved character of Holmes.

As for Rhodes, the impact of The Martyrdom upon the Ruskinite imperialist was unmistakable. Rotberg states: “Rhodes read Reade only shortly after its publication and later said that it was a ‘creepy book.’ He also said, mysteriously, that it had ‘made me what I am’” (99-100). The Martyrdom’s impact on Rhodes makes a great deal of sense when one considers its anthropological proposition that humanity is perfectible. This was a commonly held anthropological assumption among sociopolitical Utopians. After all, changing the world stipulated a fundamental change within man first. Evolutionary theory dignified the anthropological assumption of perfectibility. Darwinism was the theoretical outgrowth of an older belief system known as transformism. On transformism, organisms were infinitely mutable and could alter themselves on the essential level through a mere act of will. Pat Shipman explains:

“Transformism was a rather Lamarckian view of the mutability of species that preceded Darwinian evolution in Germany, France, and elsewhere. What connected the two theories was the essential belief that life-forms had changed over time; what separated them was the proposed mechanism, which for Darwin was natural selection and for transformists was a vaguely described will or yearning of the organism for self-improvement. However, transformism was the scientific equivalent of the French Revolution: a dangerous doctrine of the possibility of change in social as well as biological spheres. (91-92) “

Indeed, such a view could be compared to the French Revolution, which was also underpinned by the anthropological proposition of human perfectibility. That which transformism advanced in the sociological sphere would be affirmed in the realm of biology by Darwinism. Darwinism is a variety of transformism that challenges the ontological fixity of species by advancing a process in which simple life-forms metamorphose into complex life-forms through random mutations. Suddenly, organisms were divested of any determinate properties and rendered as boundlessly malleable.

This was especially true for humanity, which the Darwinian transformist believed to be just an intermediary species migrating towards a glorious developmental terminus. Nick Bostrom reiterates: “After the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), it became increasingly plausible to view the current version of humanity not as the endpoint of evolution but rather as an early phase” (“A History of Transhumanist Thought” 3).

For Rhodes, such a biological tabula rasa could be eventually shaped into the sort of citizen suitable for his dream world.

Darwinism also advanced the distinctly Manichean binary of the fit and the unfit, which accommodated Rhodes’ brutal enslavement of Africans in his quest to monopolize the continent’s diamonds. In this regard, Darwinism shares more in common with Gnosticism than its chronocentric proponents care to admit. John C. Wright states: “Ancient Gnosticism shares a contempt for the Benighted that modern Darwinians share for those races of mankind fated to fail the test of the survival of the fittest” (“C.S. Lewis, H.G. Wells and Arthur C. Clarke”).

In fact, Dr. Wolfgang Smith has characterized Darwinism as a “Gnostic myth” because it dignifies the soteriological claim of self-salvation with the metaphysical claim of self-creation (242-43). Of course, the metaphysical claim of self-creation inexorably segues into autotheism, which is the tacitly espoused religion of Rhodes’ globalist progenies. Yet, in a world ruled by earthbound gods, not everyone can be a deity. Such was the case with Rhodes’ Africa, where those whom Darwinism had declared “unfit” were either enslaved or eugenically expunged through colonial warfare. For Rhodes and his imperialist adherents, the categories of deity and mortal were demarcated according to race.

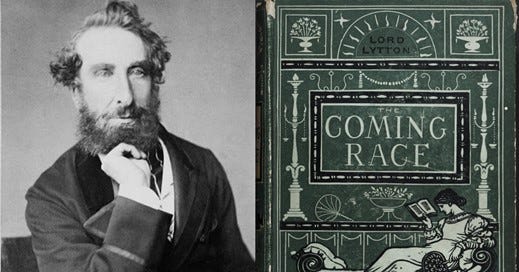

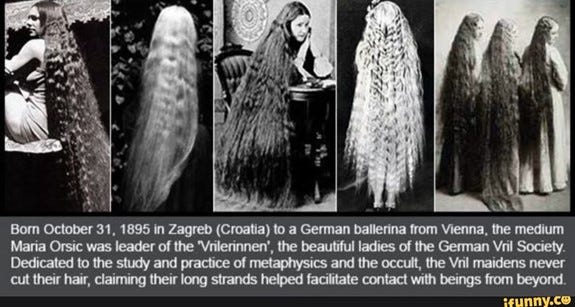

Notions of a deific race were tacitly promoted through British science fiction, as is evidenced by the work of English occultist Baron Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Baron Lytton “practiced ceremonial magic and was claimed by Madame Blavatsky to be a Theosophist” (Sklar 65).

Presumably, Baron Lytton believed that he was the keeper of a psychic energy dubbed “vril” (65). Supposedly, vril was an “electricity whose properties were the same as ‘the one great fluid’ with which all of life was pervaded” (65). According to Baron Lytton’s racial myth, an elite race of “Vril people” harnessed this divine energy through physical and mental practices similar to yoga (65). Baron Lytton promulgated this racial myth with the publication of the novel The Coming Race, which Dusty Sklar synopsizes as follows:

“Written in the nineteenth century, The Coming Race details a superhuman subterranean race of beings living in huge caves in the bowels of earth, who have developed a kind of psychic energy—vril—with which they are made the equals of the gods. They plan, one day, to take control of the earth and bring about a mutation among the existing human elite, subjugating, of course, the rest of slavish humanity.” (65)

The Coming Race inspired a transcontinental movement devoted to studying and harnessing Lord Lytton’s chimerical psychic energy. In fact, some elements of that movement would play a role in the development and rise of the Nazis.

Ominously enough, Lord Lytton referred to the deific race who mastered vril as “Aryans,” thereby adopting an appellation “already employed in European intellectual circles to identify a supposed master race of the past” (Herrick, Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs 170). Commenting on the transcontinental influence of The Coming Race, Herrick writes:

“George Edward Bulwer-Lytton used The Coming Race as a forum in which to advance his theory of a spiritually evolved master race destined to rule or destroy all other races. And his theories proved quite popular with his Victorian reading audience. Vril societies formed in England and on the European Continent, lasting well into the twentieth century. The Vril Society of Munich attracted several members who would later become prominent figures in Hitler’s National Socialist Party.” (The Making of the New Spirituality: The Eclipse of the Western Religious Tradition 147)

Baron Lytton’s The Coming Race “cemented 1 May 1871 as the formative moment of British science fiction” (Bell 207). Bulwer-Lytton’s literary work influenced many writers who used their fiction to promote global Anglo-Saxon dominion. Among them was Arthur Bennett. In his 1893 work Dream of an Englishman, Bennett provides a fictional account of the United States’ reabsorption into a revived British Empire, referred to as the United Empire of Great Britain (Bell 225). The rest of the world’s geopolitical power blocs eventually realize that they are inferior to the United Empire of Great Britain and submit to its rule, resulting in the creation of a world federation ruled by the Anglo-Saxons (226). Bennett then tips his hat to Bulwer-Lytton, asserting that the boldest members of “the coming race” were fixing their gaze upon the stars, preparing to expand Anglo-Saxon rule beyond the planet’s boundaries (226).

Of course, a world federation ruled by Anglo-Saxons would stipulate the reconciliation of the British with their racial cousins in the United States. Needless to say, there had been a considerable amount of ill will between the British and Americans since the Thirteen Colonies had achieved independence in 1783. However, an attitudinal reorientation towards the United States would eventually result in the mending of this racial rift. The attitudinal shift is literally written into the pages of British and American science fiction. The thematic shift, according to Duncan Bell, occurred in the1890s (211). Before the shift, American literature largely voiced the hostility Americans felt towards their former British rulers. Bell elaborates:

“The American choice of enemy was…. revealing. Numerous texts published during the 1880s and early 1890s portrayed a war between the United States and the British Empire, dramatizing the simmering animosity between the two countries and reflecting the deep-seated Anglophobia of large swathes of the population.” (210)

The 1890s witnessed writers radically rethinking the relationship between America and the British Empire. A drastic overhaul to the roles of villain and hero took place in order to accommodate a desire for reconciliation and reunion among the Anglo-Saxons. Many British writers envisioned an Anglo-Saxon world power where the Americans were junior partners. American writers tended to imagine the inverse, with the United States taking the reins of an Anglo-Saxon world order while the British played a secondary role. These two styles of science fiction writing share the theme of a racial union leading to a worldwide racial utopia. Bell explains:

“Many novels, both British and American, imagined the United States and the British Empire as cooperative partners, allies, or parts of a reintegrated racial-political community. They supplied cultural currency to the push for rapprochement, though symptomatic differences remained, perhaps above all in the way that the way that the relationship between the two powers was emplotted. Unlike [Andrew] Carnegie and Stead, many British authors were unwilling to yield leadership of the Angloworld – and hence the planet – to Washington, and the kin across the sea” were typically cast as an enthusiastic though immature junior partner. This attitude was mirrored across the Atlantic, where in an act of familial role-reversal Britain was usually granted a supporting role alongside a newly dominant United States. This signified both a transformation in the balance of geopolitical power and an intraracial transfer of authority, with the old idea of translatio imperii given new science fictional form.” (211; italics in original)

In his work Dreamworlds of Race: Empire and the Utopian Destiny of Anglo-America, Bell looks at a number of literary works that exhibit the unionist and Anglotopian thematic threads, starting with Frank Stockton’s successful 1889 novel, The Great War Syndicate. In Stockton’s popular tale, a heated argument regarding fishing rights touches off a war between Britain and the United States (211). A group of 23 “great capitalists” intervene in the conflict, sidelining impotent politicians who have failed to bring peace between the belligerent parties (211). Stockton’s capitalistic cabal calls to mind both plutocracy and technocracy. It will not the last time that these concepts emerge in Anglotopian science fiction.

Stockton’s story includes a plot device found in many Anglotopian science fiction pieces: destructive weapons that are used to coerce one or more belligerent parties into accepting a universal peace imposed by the Anglo-Saxons (211). In this case, the superweapons are used to force the British into surrender (211). The British are defeated, but not vanquished. The war facilitates the reunion between racial cousins, the British and the Americans (211). Bell explains:

“In an age of privatized warfare, the business leaders devise fearsome weapon systems capable of pulverizing the British, but rather than fighting their racial kin, the Americans instead demonstrate to them this newfound destructive power. Suitably apprised of their diminished status in the Anglo-American relationship, the shocked and awed British agree to serve as loyal lieutenants in “The Anglo-American Syndicate of War,” an alliance that eventually pacifies the Earth”. (211)

Stockton’s novel would become the source of inspiration for British author George Griffith’s The Pirate Syndicate (212). Griffith’s work ends with the establishment of an Anglo-Saxon federation (212). George Danyer’s 1894 novel entitled Blood Is Thicker Than Water: A Political Dream concludes with a similar union between the Americans and the British (212). The theme of racial union was taken up yet again by James Barnes’ The Unpardonable War (212). Barnes’ literary offering presents readers with yet another war between the British and Americans (212). An American victory is secured by the work of a character described by Bell as an “Edisonian inventor” (212).

The end result is an Anglo-American union (212). Roy Norton’s work The Vanishing Fleet possesses many of the unionist themes employed by Stockton, Griffith, Danyer, and Barnes. Norton imagines the Americans ushering in an Anglo-Saxon world through the deployment of superweapons, which swiftly defeat British, Japanese, and Chinese adversaries (212). The Americans, however, do not seek the total destruction of their racial kin.

Instead, the Americans extend an olive branch to the British and ask them to assist in establishing world peace (212). This results in the two Anglo-Saxon powers “pledging their formidable combined power to a new commission established to maintain international order” (212). All of these stories seemed to capture a burning desire held by Anglophile political circles. That desire was to see the divorce of 1775 successfully reversed. Bell writes: “Such texts fictionalized the debate over the possible benefits of an Anglo-American union being played out in the journals and clubrooms of the North Atlantic world” (212).

All cultural trends reach their zenith, and American science fiction with Anglotopian and unionist themes is certainly no exception to that rule. Bell states: “The American literature of racial union reached a crescendo of sorts in 1898” (212). The crescendo coincided with America’s war with the Spanish, a conflict that many regard to be a manifestation of American imperialism (212). This period of time produced Benjamin Rush Davenport’s Anglo-Saxons Onward!, a work whose title makes no attempt to hide its author’s unbridled Anglophilia (212). In Davenport’s novel, America spearheads “a ‘semi-alliance’ of the Anglo-Saxon nations to crush the Spanish empire and ultimately control the world” (212). Davenport, it seems, was exploiting the animosity that existed between America and Spain to promote Anglo-Saxon dominance. Another work authored during this time period was S.W. Odell’s The Last War; or, the Triumph of the English Tongue, which “identified genocide as a means to racially purify the earth” (212). Odell’s offering takes place in the 26th century and casts the Russians as the villains, thus capturing the anti-Slavic sentiments that seem to permeate Anglophile circles (213). An Anglo-American alliance determines that it is necessary to conduct a war of extermination against the Russian Czar and his racially intermingled empire (213). Bell writes: “Fusing racial millenarianism with the pornography of violence, millions of people are slaughtered before Anglo-American triumphs, completing the conquest of the planet” (213).

The year 1898 saw the publication of Armageddon: A Tale of Love, War and Invention (213). The novel was written by Stanley Waterloo, described by Bell as “the most famous American writer to pen a future-war narrative” (213). The novel follows the pattern found in most racial union literature, with an unprecedented crisis facilitating and alliance between America and Great Britain. Bell writes:

“Like so many novels of the future, it opens with a telescopic account of geopolitical turmoil, the Spanish-American war heralding the predestined entry of the United States onto the world stage. Yet confusion reigned and the nineteenth century, we are informed, “flickered out in something like racial warfare.” It was as if Charles Pearson’s grim predictions of global race conflict had come true. As the planet is engulfed by violence, the Americans and the British recognize their true affinities and shared interests: “the idea of an Anglo-Saxon alliance had grown and broadened.” This vision had been “fostered by thinking men of both Great Britain and America,” those who could “best foresee the future of races.” Ultimately, though, “a tentative alliance, at least, it was evident, must come.” It would form the basis of a majestic racial order.” (213)

A war ensues, with the reunited Anglo-Saxons fighting alongside the Japanese and Northern European states “against a combination of the southern ‘Latin’ races, dominated by the French and Italians (with lukewarm German support), and the ‘Slavs,’ directed by Russia” (215). Again, the old Slavic bogeyman of Anglo-Saxon fever dreams rears its ugly head.

The Anglo-Saxon alliance secures a decisive victory during “a great naval battle in the Atlantic” (215). They are assisted in their endeavor by a brilliant inventor who hails from “an isolated farm on the Illinois prairie” (213). According to Bell, this Illinois-based inventor creates “a flying machine, a cigar-shaped aluminum tube able to mount a devastating array of weapons” (213-14). Employment of this new weapon results in the destruction of the enemy armada (215). Victory is followed by a Peace Conference in Amsterdam, where the “French, Spanish, and Portuguese empires are dissolved, their territories transferred to the more deserving Anglo-Saxons” (216).

Many writers of science fiction with racial union themes entertained the notion of an imperial federation ushering in a racial utopia. Julius Vogel, asserts Bell, “wrote the most interesting novel on the subject” (218). Regarding Vogel, Bell writes:

“Vogel was an ardent supporter of the imperial federation movement, arguing that without formal consolidation the British Empire would ultimately dissolve, reducing the mother-country to the status of a second-rate power and leaving the colonies at the mercy of larger predatory states” (218).

Vogel’s 1889 work, Anno Domini 2000, reflects the desire of some Anglophile circles to facilitate the rise of an Anglotopia through imperial federation. In Vogel’s literary universe, a waning British Empire’s very existence is imperiled in the 1920s by a dispute centered around Ireland (221). The empire resolves the problem through the federation of the empire (221). There is a reconfiguration of the empire “as power drains away from the old imperial center without precipitating the dissolution of the whole” (221). Bell elaborates:

“Decline is followed by rebirth rather than Fall. Vogel’s Anglo-imperium is figured immune to traditional causes of degeneration, at once too large for external assault and too internally robust for corruption to corrode it from within. Imperial federation thus allows the reconciliation of grandezza and libertas – imperium could permanently escape the vicissitudes of historical time. Vogel can present London as partially corrupted by luxury, its inhabitants “chartered sybarites” and “luxurious to the verge of effeminacy,” but rather than serving its classical role as the primary agent of decline, such hedonism is rendered harmless, even comic, because of the dispersal of political authority and economic might. The British dominions have been consolidated into the empire of United Britain; and not only is it the most powerful empire on the globe, but at present no sign is shown of any tendency to weakness or decay.” (221-22)

Vogel’s Anglo-Saxon empire is also strengthened through the adoption of technocratic practices. This transformation of the empire into a technocracy leads to unprecedented technological progress and the ascendancy of the Anglo-Saxon race. Bell writes:

“Political unity was predicated on technoscientific progress. Following the wise intervention of the Prince of Wales, the citizenry is no longer distracted by having to learn useless dead languages, but are instead given an intense practical scientific training, with the result that “each person was more or less an engineer.” More typically American than British, this Wellsian mode of subject formation further accelerated technological progress. The novel is studded with inventions – “phonograms,” force fields, aluminum air cruisers. At one point, people are rendered immobile by a mysterious but devastating weapon that harnesses the power of electricity. Portable silent “hand telegraphs” allow journalists to stream live accounts of political debate across the polity, creating a powerful sense of instantaneity and communal identity. Vogel’s novel exemplifies the fascination with infrastructural space, racial informatics, and communications systems that suffused the discourse of Angloworld unification. It imagines the Anglo-Saxon race as a cyborg assemblage, knitted together by a dense communications network pulsating with information. The transformative potential of communications technology is reinforced by new modes of aerial transport. Global geography is rewritten. “A journey from London to Melbourne was looked upon with as much indifference as one from London to the Continent used to be.” Confined to use by the government – in contrast to many American novels of the era – this airpower underwrites British military superiority over other states. We are informed that these mighty sentinels “made easily a hundred miles an hour” across the skies of the future.” (222)

Vogel pits the British Empire, reinvigorated by a federation model of management and technocratic practices, against the United States (223). This conflict is touched off by “dynastic dispute between the British Empire and the United States” (223). Vogel’s fictional war, however, is not meant to bring about the destruction of America. It, instead, acts almost like a Hegelian dialectic, synthesizing the two belligerent parties and giving rise to a reunified federated empire. Bell provides a summary of the contest between racial cousins and the end result:

“The Americans launch an impetuous attack on Canada only to be swatted aside like flies, before a vast British armada is sent across the Atlantic to punish them. The expeditionary force captures Washington and proceeds to outflank the American army in Canada. They demonstrate their abiding sense of kinship by refusing to massacre the brave but ineffectual American soldiers – presumably a fate reserved for the hapless “natives” that the empire continues to govern. The forlorn President is whisked aboard the advanced air-cruiser The British Empire, and the British celebrate “a triumph which amply redeemed the humiliation of centuries back, when the English colonies of America won their independence by force of arms.” The injustice of history redressed, the door is opened to reuniting Anglo-America. The terms of the subsequent peace deal include a plebiscite in New England, where the inhabitants vote overwhelmingly to (re)join the British Empire, with New York anointed the new capital city of the Dominion of Canada. The democratic empire is extended democratically. In a mirror image of many American tales, the United States – or at least the authentic “Anglo-Saxon” element – is simultaneously reincorporated into the Angloworld and assigned a subordinate position within it. It has been transfigured from a powerful independent state to a region within British imperial jurisdiction.” (223)

Vogel and scores of other unionist science fiction writers emphasized the reunification of racial cousins and the revival of empire. Other writers in the bizarre Anglotopian genre, however, stressed a supposed racial salvation found in the Anglo-Saxon race. Authors like George Chetwynd Griffith and Louis Tracy “posited the Anglo-Saxons as redemptive saviors of civilization” (226). In The Angel of the Revolution, Griffith envisioned the Anglo-Saxons saving humanity with “socialist Anglo-future” (227). Tracy, on the other hand, wrote The Final War in 1896, which saw the Anglo-Saxons’ salvific power wrapped in “the existing imperial capitalist order” (227). Through the medium of literature, Anglo-Saxons acquired a messianic mystique. The apotheosis of the Anglo-Saxon elite had been realized through the power of the pen.

Fact Abolished and Fiction Made Flesh

It is not surprising that the sociopolitical Utopians of Rhodes’ tradition carried on such an extensive reciprocal relationship with British sci-fi authors. Both adhered to a hermeneutical tradition steeped in a cannibalizing epistemic incredulity. The British sci-fi authors were deeply mistrustful of the cosmos because, according to the Baconian formulation of modern science, the universe was nothing more than a standing reserve of malleable material (Bestand as Heidegger put it). Ergo the cosmos was an ontologically suboptimal simulacrum. Meanwhile, Rhodes’ imperialist progenies were deeply suspicious (and forthrightly contemptuous) of the social cosmos because its inherent heterogeneity violently conflicted with their dream world of political, economic, and racial homogeneity. Ergo the social cosmos was an ontologically suboptimal simulacrum. This shared hermeneutical tradition was merely an echo of the cosmological resentment espoused by the ancient Gnostics.

Yet, Rhodes’ disciples and their fellow travelers in the literary world parted ways with their ancient antecedents concerning their response to the cosmos. While the ancient Gnostics sought to escape the world, Rhodes’ imperialist progenies sought to transform it. Envisioning an Eschaton in history, Rhodes and his Anglophilic crusaders adopted the Hegelian rallying call: “That which is cannot be true.” The facts of established reality had to be abolished so that the Utopian fiction of Rhodes’ mind could be made flesh. British sci-fi scribes merely committed Rhodes’ Utopian fiction to paper. Years later, the globalist offspring of Rhodes would continue to incarnate some variant of that Utopian fiction. Predictably, many modern science fiction authors continue the tradition of their British precursors by rendering the globalist dream world as an inescapable inevitability. Jutta Weldes elaborates:

“The neo-liberal discourse of globalization dominating public discussion is a self-fulfilling prophecy that rests on a well-rehearsed set of narratives and tropes, including an Enlightenment commitment to progress, the wholesome role of global markets, a rampant technophilia, the trope of the “global village,” and the interrelated narratives of an increasingly global culture and an expanded pacific liberal politics… this discourse displays striking homologies to American techno-utopian SF [science fiction]… These homologies help to render neo-liberal globalization both sensible and seemingly “inexorable.” (Weldes, “Popular Culture, Science Fiction, and World Politics” 3)

In light of these homologies, it is not difficult to understand why the popularization of certain sci-fi myths is so advantageous to the global oligarchical establishment. These myths both propagate and affirm “a well-rehearsed set of narratives and tropes” that undergirds global governance. Through the sci-fi literary genre, the power elite’s fanatical eschatological vision for world order is not only rendered tenable, but inexorable. Yet, the globalist dream world is neither tenable nor inexorable because it does not comport with the structure of reality. Reality will continue to relentlessly assert itself, rudely awaking the inheritors of Rhodes’ Anglotopian dreams.

Sources Cited

Bartter, Martha A. “Normative fiction.” Science Fiction, Social Conflict, and War, Philip John Davies, ed. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1990, 169-85.

Bell, Duncan. Dreamworlds of Race: Empire and the Utopian Destiny of Anglo-America. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 2020.

Bostrom, Nick. “A History of Transhumanist Thought.” Nick Bostrom’s Home Page 21 February 2006 <http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/history.pdf>

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Sign of Four. 1890. Project Gutenberg. Web. Aug. 2023 <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2097/2097-h/2097-h.htm#chap02>

“Francis Marion Crawford.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia 29 April 2024 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Marion_Crawford>

Herrick, James A. The Making of the New Spirituality: The Eclipse of the Western Religious Tradition. Downer’s Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2003.

—. Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs. Downer’s Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2008.

Katsiaficas, George and Mary Lou Emery. “Critical Theory and the Limits of Sociological Positivism.” Transforming Sociology Series. 1978. Red Feather Institute 2008 <http://www.tryoung.com/archives/176krkpt.htm>

Quigley, Carroll. Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in our Time. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Rotberg, Robert. The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. New York: Oxford UP, 1988.

Shipman, Pat. The Evolution of Racism. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Skelton, Charlie. “Silicon Assets.” Flaunt Magazine 22 September 2015 <http://www.flaunt.com/content/art/silicon-assets>

Sklar, Dusty. The Nazis and the Occult. New York: Dorset Press, 1977.

Smith, Wolfgang. Teilhardism and the New Religion: A Thorough Analysis of the Teachings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Illinois: TAN Books, 1988.

Weldes, Jutta. “Popular Culture, Science Fiction, and World Politics.” To Seek Out New Worlds: Science Fiction and World Politics, Jutta Weldes, ed. NY: Palgrave, 2003, 1-27.

Wright, John C. “C.S. Lewis, H.G. Wells and Arthur C. Clarke.” Live Journal 21 April 2009

<http://johncwright.livejournal.com/243016.html>

About the Authors

Phillip D. Collins acted as the editor for The Hidden Face of Terrorism and co-authored the books The Ascendancy of the Scientific Dictatorship and Invoking the Beyond: The Kantian Rift, Mythologized Menaces, and the Quest for the New Man. Both books are available at

http://www.amazon.com

. Phillip has also written articles for News With Views, Conspiracy Archive, and the Vexilla Regis Journal.

In 1999, Phillip earned an Associate degree of Arts and Science from Clark State Community College. In 2006, he earned a bachelor’s degree with majors in communication studies and liberal studies along with a minor in philosophy from Wright State University.

Phillip worked as a staff writer for a weekly news publication, the Vandalia Drummer, between late 2007 and 2011. During his tenure with the paper, he earned several accolades.

In 2011, he was inducted into the Media Honor Roll by the Ohio School Board Association for his extensive coverage of the Vandalia-Butler School District. That very same year, the Ohio Newspaper Association bestowed an Osman C. Hooper Newspaper Award upon Phillip for Best Photo. In addition, the City of Vandalia officially proclaimed that November 7, 2011 would be known as “Phillip Collins Day.” This honor was bestowed upon Phillip for his tireless coverage of the City and community.

Shortly after bringing his journalism career to a close, Phillip received another Osman C. Hooper Newspaper Award in the category of In-depth Reporting. This award was given to Phillip for his investigative work over the death of U.S. Marine Maria Lauterbach and the resultant Department of Defense reforms concerning sexual assault and rape. The case drew national attention and received TV coverage by major media organs.

Paul David Collins is the author of The Hidden Face of Terrorism and the co-author of The Ascendancy of the Scientific Dictatorship and Invoking the Beyond: The Kantian Rift, Mythologized Menaces, and the Quest for the New Man. In 1999, he earned his Associate of Arts and Science degree from Clark State Community College. In 2006, he received his bachelor’s degree with a major in Liberal Studies and a minor in Political Science from Wright State University. He worked as a professional journalist for roughly four years.

From 2008 to 2012, Paul covered local news for several Times Community News publications, including theEnon Messenger, the New Carlisle Sun, the Tipp City Herald, the Kettering/Oakwood Times, the Beavercreek News Current, the Vandalia Drummer, the Springboro Sun, the Englewood Independent, the Fairborn Daily Herald, and the Xenia Daily Gazette.

Paul also wrote for other local papers, including the Enon Eagle, the New Carlisle News, and the Lusk Herald. In addition to his work in the realm of mainstream, Paul has published several articles concerning the topics of deep politics and elite deviancy. Those articles have appeared in Terry Melanson’s online Conspiracy Archive, Paranoia magazine, Vexilla Regis Journal, and Nexus magazine.